11月10日,经济学人发布该文,点击“中英对照”可查看英文原版。

老挝,一个仅有6百万人口的贫穷国家,地处越南和泰国之间。它没有沿海的港口城市也几乎没有得到世界关注的理由。但是,现在的老挝正在阳光下享受着难得的机遇。上个月,它成功加入了世界贸易组织。本周,它主办了第九届亚欧首脑峰会,该会议汇集了世界上最具活力和最欠活力地区的领导人。老挝对外出口黄金,铜金属和水力电力。尽管老挝是一个规模极小的经济体,但它是世界上经济增长最快且最稳定的国家之一。

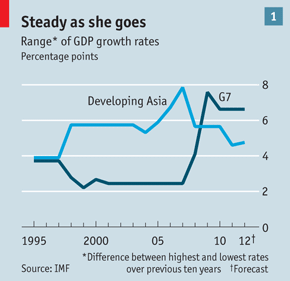

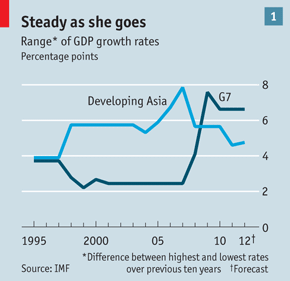

在2002至2011年之间,老挝的经济增长率在一个非常狭窄的范围内波动,GDP年增长率从未低于6.2%,从未高于8.7%。在此期间,全球只有三个国家保持着更加稳定的经济增长速度。其中的两个是亚洲的印尼和孟加拉国。亚洲发展中国家的经济增长与G7所代表的成熟经济体相比更加平稳且更加迅速。(详见下表,蓝线代表亚洲发展中国家在1995至2012年期间的GDP增幅,黑线代表G7在同期的GDP增幅。)

“大缓和”(Great Moderation)这个词是在金融危机之前用来形容美国及其他富裕国家经济稳定时期的特定名称。这个标签现在可以贴到亚洲身上吗?

亚洲经济体通常以较高的经济增长速度而闻名世界,但其经济增长稳定性却欠佳。例如,在1996至1998年之间,受到东南亚金融危机的影响,五大东南亚国家(印度尼西亚,马来西亚,菲律宾,泰国和越南)的经济增长率在正7.5%至负8.3%之间摇摆。就目前而言,即使是那些高度开放的经济体,如泰国,新加坡和台湾,经济增长波动仍高于全球平均水平。由于受到全球贸易流动的影响,其工业总产值伴随着需求的变化而像高速旋转的丝带般(twirling ribbon)剧烈波动。

但是亚洲的经济发展(不包括亚洲的富裕经济体,例如香港,新加坡,韩国和台湾)受到靠内需拉动经济的人口大国的主宰。在今年前三季度,家庭消费为印度尼西亚贡献了一半的GDP增长率。印尼的出口总量在十年前约占GDP的35%,在2011年,印尼的出口总量占GDP比重下降至不足25%。亚洲的发展中国家经常账户盈余的总额(该数字反映出国家经济对国外需求的依赖程度)在2008至2011年间减少了一半以上,预计今年将出现进一步下跌。

亚洲的稳定应在一定程度上归功于亚洲人对经济事务的管理。在亚洲金融危机期间,亚洲的经济决策者们面临着两难的境地。他们可以通过提高利率以捍卫汇率。但这将为他们从外国借款增加障碍。或者,他们可以通过下调利率使本国货币汇率下跌。但是,这将提高外债水平,同样为借款增加了障碍。

在危机之后,亚洲通过自己的方式逐步走出危机的陷阱。很多国家都积累了大量的硬通货储备(hard currency reserve),同时逐步清偿本国在外资银行所欠的债务。因为这些负债通常以负债国本国货币进行定价,因此负债额并没有因为本国货币的贬值而出现上升。

这种现象驱使亚洲的政策制定者们在经济增长放缓时下调利率。例如,印尼央行曾在2008年12月至2009年8月间降息3个百分点。在2011年10月至2012年2月间,印尼央行再次下调利率1个百分点。由于其央行的正确决策和操作,在过去的五年中,印尼一直是GDP同比增长率最稳定的国家。

正确的货币政策也是G7实现经济“大缓和”的原因之一。另一个导致“大缓和”的原因是世界富裕国家金融系统的深度和复杂性。这个成熟的系统帮助家庭控制消费,帮助企业拓展债务结构,帮助银行降低资产负债表的困扰。

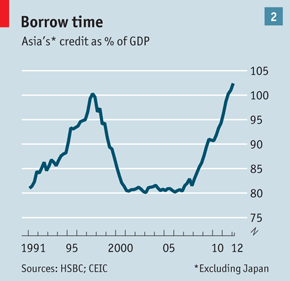

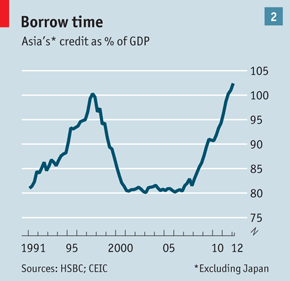

令人担忧的是,亚洲的经济“大缓和”,通常也伴随着债务水平的急剧上升。汇丰银行经济学家Fred Neumann认为,当前亚洲的杠杆率达到亚洲金融危机以来的最高点。(下图展示了1991年至2012年间亚洲国家负债水平占GDP比重的变化走势)。这样的信贷扩张可能象征着健康的“金融深化”(financial deepening),许多经济学家认为这是经济增长和经济稳定的原因之一。但是,日益上升的杠杆率也可能对经济稳定造成威胁。已故的美国经济学家Hyman Minsky认为,经济波动的企稳将允许企业和家庭获得更多借款以进行投资。在Minsky的模型中,稳定的经济最终会变得不稳定。过高的财务杠杆无法通过更加乐观的情绪来维持,只能通过增加经济确定性来维持;运用财务杠杆的目的并非经济的快速增长,而是经济的稳步增长。

幸运的是,亚洲的政策制定者们从来没有接受西方所信仰的金融体系可以“自我修复”的观念。亚洲率先从宏观角度对金融体系进行审慎的监管。此举的目的是,在不提高利率的情况下,抑制过度的信贷投放和资本流动。例如,今年3月,印度尼西亚降低了住房贷款的抵押贷款批准率(loan-to-value ratio),同时为汽车购买者贷款时需要偿付的定金设置下限。

Neumann对“增强监管可以替代货币政策”的观点持怀疑态度。他认为,宏观监管并非是无懈可击。如果融资成本较低,资金就会流动。如果监管机构降低了抵押贷款批准率,银行可能将通过提高家庭住房的评估价值(apprised value)来规避监管。如果监管机构阻扰外资购买本国物业,就如同香港的所作所为一样,外国投资者将通过别出心裁的方式以绕过资本监管。

港币汇率的浮动受制于港币与美元挂钩的联系汇率制度,香港是为数不多的成功克服亚洲金融危机的地区之一。对其他国家(地区)而言,货币政策的灵活性驱使他们在经济增长放缓时降低利率;也允许他们在受到金融系统流动性过剩的威胁时提高利率。Neumann认为:如果稳定的经济增长允许贷款人或借款人过度借贷,他们将“播下导致自身毁灭的种子”。

LAOS, a poor country of 6m people wedged between Vietnam and Thailand, has no openings to the sea and few routes to world attention. But it is now enjoying a rare moment in the sun. Last month it won approval to join the World Trade Organisation. This week it hosted the ninth Asia-Europe meeting, which brings together leaders from the world’s most and least dynamic regions. Its small economy, which exports gold, copper and hydropower, is distinguishing itself. Its growth rate is not only one of the fastest in the world but also one of the steadiest.

From 2002 to 2011 growth fluctuated within a remarkably narrow range, never falling below 6.2% and never rising above 8.7%. Only three countries have recorded a steadier growth rate (as measured by its standard deviation) over that period. Two of them are also Asian: Indonesia and Bangladesh. Growth in developing Asia is now steadier, as well as faster, than growth in the “mature” economies of the G7 (see chart 1). It was more stable in 2002-11 than over any other ten-year span since 1988-97.

The “Great Moderation” is the name given to the era of economic tranquillity that prevailed in America and elsewhere in the rich world before the financial crisis. Should the label now be applied to Asia?

Asia’s economies are better known for their speed than their stability. From 1996 to 1998, for example, growth in five big South-East Asian countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam) swung from 7.5% to minus 8.3% as the Asian financial crisis struck. Even now some highly open economies, such as Thailand, Singapore and Taiwan, remain more volatile than the global average. Exposed to international trade flows, their industrial output fluctuates like a twirling ribbon with every twitch of demand.

But developing Asia (which excludes rich economies like Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan) is dominated by populous countries that rely increasingly on domestic demand to drive their economies. Household consumption contributed half of the growth of just over 6% Indonesia enjoyed in the year to the third quarter (its eighth consecutive quarter of growth at that pace). Exports have fallen from about 35% of GDP ten years ago to less than a quarter in 2011. Developing Asia’s combined current-account surplus, which reflects its dependence on foreign demand, more than halved from 2008 to 2011 and is expected to fall further this year.

Asia’s stability also owes something to demand management. During the Asian financial crisis policymakers faced a dilemma. They could defend their exchange rates by raising interest rates. But that would cripple borrowers. Or they could let their currencies fall and ease rates. But that would inflate the burden of foreign-currency debt, crippling borrowers too.

In the aftermath of the crisis the region worked its way out of this trap. Most countries accumulated an impressive stock of hard-currency reserves and weaned themselves off foreign-bank loans in favour of foreign equity and local-currency bonds. Because these liabilities were denominated in their own currency, they did not rise in value when the currency fell.

That has freed policymakers to cut interest rates when the economy slows. Indonesia’s central bank, for example, slashed rates by three percentage points from December 2008 to August 2009. It cut rates by another point from October 2011 to February 2012. Thanks in part to its responsive central bank, Indonesia’s year-on-year growth rates over the past 20 quarters have been the most stable in the world.

Wise monetary policy was also one of the reasons cited for the Great Moderation enjoyed by the G7 economies. Another was the supposed depth and sophistication of the rich world’s financial systems, which, it was said, allowed households to smooth their spending, firms to diversify their borrowing and banks to unburden their balance-sheets. Both of these pillars of stability proved false comforts. Economists had not quite settled on an explanation for the Great Moderation before it inconveniently ceased to exist.

Worryingly, Asia’s great moderation has also been accompanied by sharply rising credit. According to Fred Neumann of HSBC, leverage is now higher than at any time since the Asian financial crisis (see chart 2). This credit expansion may represent healthy “financial deepening”, which many economists believe is a cause of growth and stability. But rising leverage can also be a threat to stability. The late Hyman Minsky, among others, argued that drops in volatility allow firms and households to borrow more of the money they invest. Stability, in Minsky’s formulation, eventually becomes destabilising. Overleverage does not require excessive optimism, merely excessive certitude; not fast growth, merely steady growth.

Fortunately, Asia’s policymakers never shared the West’s faith in self-correcting financial systems. The region has pioneered “macroprudential” regulations, designed to curb excessive credit and capital flows even without raising interest rates. In March, for example, Indonesia tightened loan-to-value ratios on mortgages and imposed minimum downpayments on car and motorbike loans.

Mr Neumann is, however, sceptical that regulatory tightening can substitute for the monetary kind. Macroprudential controls are not watertight, he notes. As long as capital remains cheap, money will leak. If the regulator lowers mortgage loan-to-value ratios, for example, banks may simply raise the appraised value of a home. If regulators impede foreign purchases of property, as Hong Kong just did, foreigners will seek inventive ways around the rules.

Hong Kong’s freedom to raise rates is constrained by its currency’s fixed link to the dollar, one of the few pegs to survive the Asian financial crisis. Other central banks do not have that excuse. Currency flexibility has given them the freedom to cut rates when growth slows. It should also allow them to raise rates when financial excess threatens—even if rates remain near zero in America, Europe and Japan. If stable growth allows lenders or borrowers to become overstretched, it can “sow the seeds of its own destruction”, Mr Neumann argues. Nothing great about that.